We started Sunday with a team ritual: reading poems aloud. Some were fun, some serious, all genuine. Afterward came “call-outs,” where team members recognized each other’s efforts, followed by a weather update—crucial for planning fieldwork in the Arctic. These routines, carried out without fuss, reflected how much intention goes into maintaining a strong team culture.

That intention showed up in both small and big ways throughout the week: jokes called out and laughter lightened long days. One evening, for example, we gathered around a bonfire. As the wind howled through the beach, we enjoyed warm hands and bright sunshine—the pleasures of the eternal light of summer!

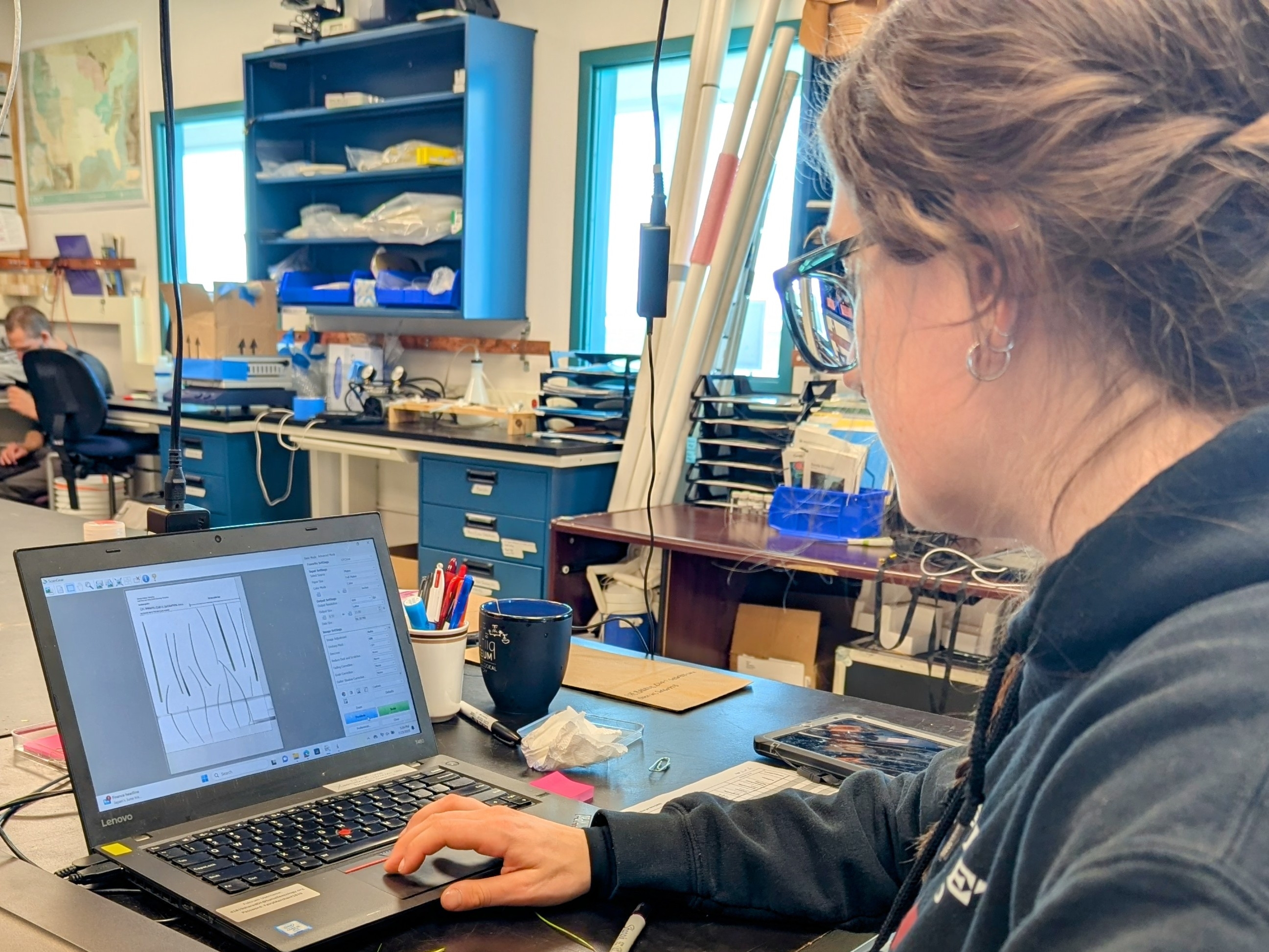

In the field, my second week kicked off with three protocols: plant biomass collection, chlorophyll extraction, and analysis of leaf mass per area (LMA) and foliar chemistry, including carbon, nitrogen, and lignin. For each, we harvested all green plant material from selected plots, then divided it for different types of analysis. When handling chlorophyll samples, only nitrile gloves were allowed to prevent contamination—even in the wind. The team stayed upbeat while finding creative ways to shield the samples from blowing away, building little windbreaks with their bodies or using gear as barriers to keep everything stable.

On my final day, I joined Maddie and Matthew. Their work revolves around phenology —the timing of biological events like growth and flowering. Each week, they revisit the same 100 plants: 20 species, with 5 replicates per species. They track growth, development, and reproductive stages. As we moved between plants, I asked what they’d noticed over the years. Matthew, who grew up in Utqiaġvik, said this spring had been colder and drier than usual. Maddie, who’s been with the project for four seasons, noted that the grasses weren’t greening up as they normally do. Their observations felt deeply valuable—and made me wonder how anecdotal knowledge like this might be incorporated into advancing ecological research. There’s something powerful about connecting long-term data with the insights of people who live closely with the land.

This question about changes stayed with me. Later that week, I asked Will, the team’s lead, what he had noticed during his studies in the Arctic. He spoke about the delicate balance between moss and woody shrubs. Moss retains moisture and prevents soil erosion in summer. In winter, it shrinks back, allowing the ground to cool and helping maintain the frozen permafrost below. Meanwhile, he’s observed an increase in woody shrubs around their Toolik field station. As the snow melts earlier each year, these shrubs have more time to grow. When snow falls, shrubs trap and hold it in place, creating an insulating layer that doesn’t blow away. This insulation keeps the ground warmer, which can potentially contribute to permafrost thaw. Additionally, by blocking sunlight, shrubs also limit moss growth. This creates a positive feedback loop: warmer soils promote more shrub growth, which in turn traps more snow and keeps soils warmer still—accelerating changes in the tundra landscape.

As Will and I reflected on my experience, he pointed out how this had been a good opportunity to think about the “why” of this work—not just the methodology, but what we are trying to uncover. What do these measurements tell us about the changing Arctic ecosystems? What can they reveal about broader environmental patterns? That curiosity—about the “why” and the “so what”—is something I want to bring back.

When the project came to a close, our plane lifted off one evening, and I looked out the window at the land and sea below. I thought about how, in the winter, the frozen ocean becomes a highway—a surface that connects. So much of this place revolves around the ice. On the land, it preserves layers of water, soil, and organic matter. On the sea, it reflects sunlight and cools the planet. In both forms, it holds things together.

Thinking about the importance of ice, my mind returns to the times we crossed small rivers and stretches of flooded tundra to reach our research plots over the past two weeks. At first, I wasn’t sure my waders and gaiters would hold up. Or whether I could stay upright as I slowly sank into the soft ground. But with each step, I grew more confident—and more curious.

Then, just beneath the spongy surface, my boots met something firm and slick: the permafrost. I knew I was touching something essential—not just for this ecosystem, but for the planet. That quiet moment felt almost like an introduction. There you are. I’ve been hearing so much about you.

Now that I’ve stood on this land and felt the rhythms of the Arctic, I’m committed to continuing the learning—and to bringing it back to my students. I hope to share this place with them through the stories I carry home: the moments, the questions, the quiet discoveries. I want them to notice what’s hidden, what’s changing, and what endures—to ask how it works, and why it matters.

I want to extend my heartfelt thanks to NEON Flora in Fairbanks for their incredible support and hospitality, which made this journey possible. I’m also deeply grateful to the Polar STEAM program for their thoughtful preparation and attention to detail that made this trip truly perfect. This experience has had a profound impact on me and will continue to shape my work and teaching.