My journey starts at Toolik Field Station (TFS), a research station located 370 miles north of Fairbanks, Alaska at Toolik Lake with an interdisciplinary group of Co-Principle Investigators (Co-PIs) and graduate students from three different institutions. As Arctic permafrost thaws, carbon that has been sequestered, or frozen in the ground for thousands of years, can be released into the air as carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane gas (CH4). This project explores why carbon release may happen more intensely in sudden bursts/hot-moments, or in specific locations/hot-spots, rather than evenly across the landscape. By studying how plants, soils, and microbes interact as permafrost thaws, the research will improve our ability to predict when and where carbon will be released over time. These insights will help scientists and decision-makers better understand long-term effects of permafrost thaw on the Earth’s carbon cycle.

TFS provides science support to researchers and students across the globe by providing access to laboratories, a research helicopter, Geographic Information System (GIS) and mapping services, technical and IT assistance, common analytical equipment, a collection of standardized data, in addition to housing and meals. It’s a great place to make points of connection with other researchers who are doing research in the same area. For those of us heading out into the field for an extended time, it is an important haven for a bed, hot meal, and a sustainable hot shower! Note for those staying extended times at TFS, only two, 2-minute showers a week is considered sustainable. Water conservation is essential due to the logistics and cost of hauling wastewater from a remote location.

The saying “It’s not the destination, it’s the Journey” retains its validity when embarking on a robust, interdisciplinary research project in the field of the Arctic tundra. Helicopter drops were literally the only way to get to our remote field site adjacent to a drained lake, colloquially named Lake 69. The area was preselected for its variety of landscapes and sampling sites. All of the research equipment, camping gear, and living essentials were literally dropped in the middle of the field.

The next order of business was to set up base camp. This would be our central station while in the field going back and forth daily to test sites near the field camp. In addition to having our team meetings and team meals here, the base camp is intended to provide a reprieve from the insufferable number of mosquitos. Before nightfall, we also needed to set up our personal sleeping tents, and place all food, snacks, toiletries and all smellables within the electrified bear fence. The bear fence was located away from our tents but closer to the family tent. There could not be anything to attract a bear to ourselves. Certainly all food would be considered, but also toiletries and items labeled fragrance free because even if it is a smell undetectable to humans, bears could still have a reaction to it.

No photo or video can accurately convey the intense level of mosquitos present during this field work. For others who had worked in the area before, it was a 10 out of 10 for mosquitos activity. I basically lived in a mosquito shirt with built in head net. Couple that with the temperature being unseasonably warm, even for the summer months, around 70°F. Let’s just say all of these factors added to my Arctic tundra adventure!

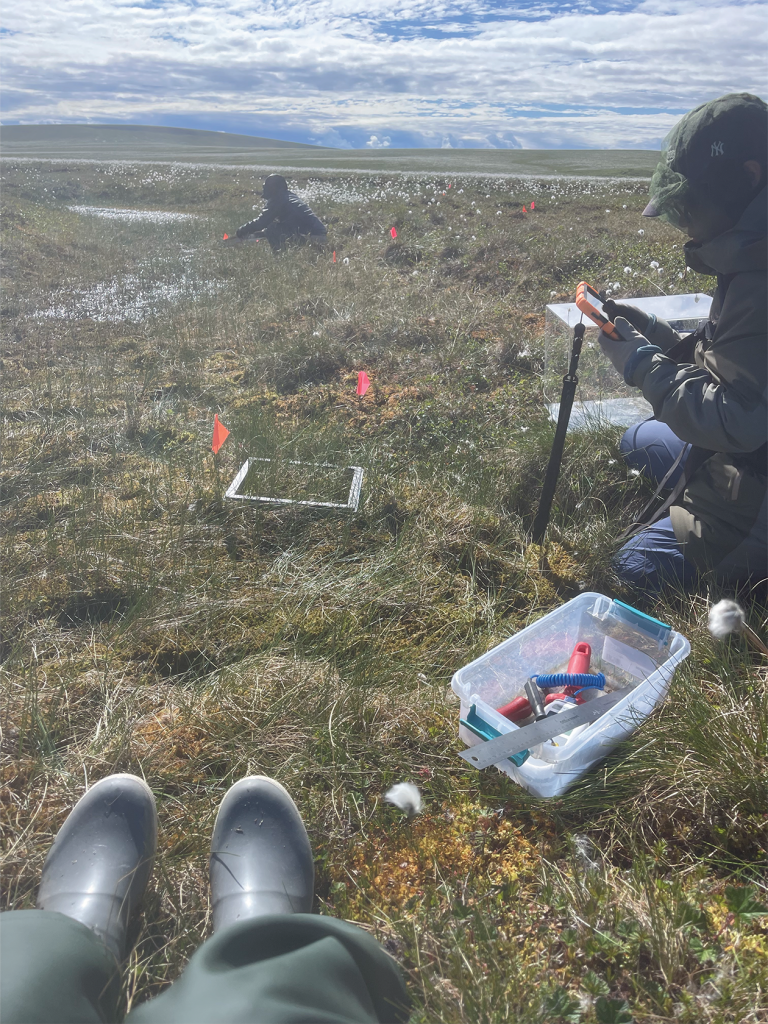

With such a multi-scale project, I had the fortune of seeing all of the aspects of fieldwork. First, I worked with Co-PI Jen and graduate student AJ hiking out to survey sites in sections A, B, and C. Measurements of temperature of sub soil, moisture content, depth of soil to permafrost, and percent of different species of plants per 3×3 quadrant were recorded.

I spent multiple days working with graduate students Lijia and Morgan. This work was central to the project, measuring CO2 and CH4 gas fluxes at intensive sites. We used custom-designed chambers placed atop square collars to measure these gasses under light, shaded and dark conditions. At each site, we manually recorded surface and subsurface soil temperatures, the average collar insertion depth, and photosynthetically active radiation (PAR), a light exposure measurement which quantifies the light intensity available for photosynthesis. These manual measurements provide more context for the conditions in which gas fluxes are being measured. The gas flux measurements are central to this research, because they directly reveal how carbon is moving between the land and the atmosphere and how this movement responds to environmental conditions.

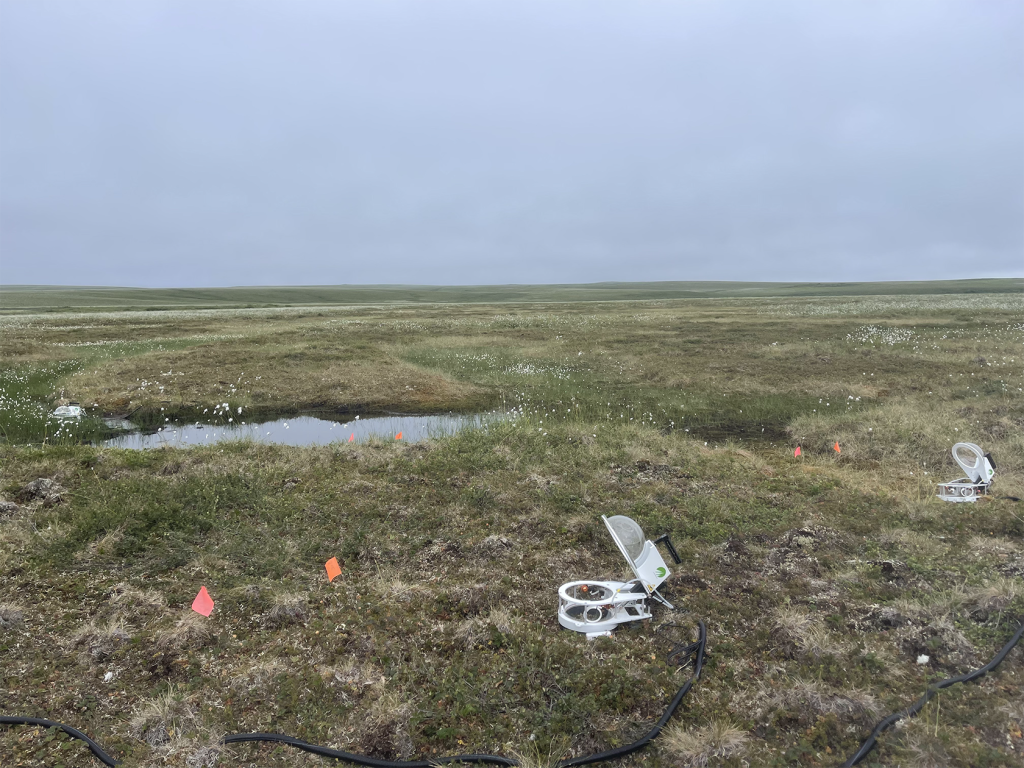

In addition to the manual site readings (pictured above), solar powered auto chambers were utilized for hot-spot continuous readings of CO2 and CH4 gases (pictured below). Hot-spots are small areas where gas emissions, namely CO2 and CH4, are much higher than the surrounding landscape, often driven by plant inputs, soil conditions, localized microbial activity and most importantly permafrost degradation. The auto chambers were powered by portable solar panels to continuously measure gas fluxes at the specific field sites. We were able to log nearly 7 days of continuous data using this process.

A different perspective was gained partnering with my primary collaborator, Polar STEAM Researcher Fellow and PI Mark Lara as he navigated a drone customized with sensors measuring CH4 and CO2 emissions. This drone was wired with GPS to capture information regarding speed, direction, tilt, and a mobile weather station that measured temperature, wind speed, and direction. Collectively, this system can then calculate the footprint on a macro scale of the landscape and where the green house gases (GHG) are being emitted in real time.

I continued to observe more drone activity with Co-PI Christian and graduate student Katie performing thermal surveys of sites. Another drone was equipped with a Red, Blue, Green (RGB) camera capturing photos every 2 seconds within the footprint of the site. The drone was also equipped with an infrared (IR) camera to capture surface temperatures of the landscape. Nearly 800 photos per site can then be uploaded onto structure for motion photogrammetry software which stitches all the photos together and gives an average of thermal signature output. An elevation model of the landscape utilizing the GPS locations of the drone is another output. The manual temperature sensors in the field were recording actual surface and soil temperatures for validation to make certain thermal map of the surface derived from drone is accurate. This thermal map of the surface will be coupled with soil temperature measurements to model the temperature of soil and model the thermal properties of permafrost.

Co-PIs Mario and Christian were tasked with collecting sediment cores at each of the intensive sites. The cores were kept frozen in a makeshift underground freezer ( the permafrost pit) until transferring back to the lab at TFS.

Time to pack up the camp site and helicopter out. Amazing how much quicker the break down goes in comparison to setting up. The chopper ride allowed another great vantage point to see the Arctic tundra as we approached the mountains surrounding the TFS. The mission was a success! A wonderful opportunity to be on the front line of an interdisciplinary research project advancing the bodies of knowledge of past and projected carbon cycle dynamics as well as key biogeochemical consequences of permafrost thaw. Note that permafrost is the largest carbon store on land, holding nearly twice as much carbon as is currently in the atmosphere, and more than twice as much carbon as all the world’s trees, therefore changes to it could have a major impact on how carbon cycles through the environment. This research is important because understanding how permafrost stores and releases carbon helps us predict changes in ecosystem and global biogeochemical cycles.

Back in the lab at TFS, Co-PI Jen and AJ were leading the team in sorting, dividing and labeling all of the samples obtained at the field sites. Everyone got their hands dirty. Dwarf shrub, graminoid, lichen, forb, moss, standing dead, and litter were some of the most prevalent categories for materials sorted. These samples traveled back to the respective Co-PI’s laboratories for further micro-scale analysis. From the initial analysis, we hope to see how plants and microbes work together in permafrost soils to control carbon. As permafrost thaws, microbes break down stored organic matter, and plant roots can influence where and how this happens.

In conclusion of an amazing exploration in the Arctic tundra researching biogeochemical cycle dynamics related to permafrost thaw, I’d like to thank Polar STEAM and U.S. NSF for the opportunity to participate as a 2025 Educator Fellow. In respect to Mother Earth and the land, I’d also like to acknowledge the Alaska Native nations upon whose traditional lands the TFS operates. Acknowledgement that the grounds surrounding TFS are located on ancestral hunting grounds of the Nanamiut, and occasional hunting grounds and routes of the Gwich’in, Koyukuk, and Iñupiaq people is imperative. Much gratitude to the Indigenous people who inhabit and are stewards for the land.