Meet the Team

I am so grateful that during my time in the field, I was part of such an incredible team. When it comes to remote field work, the dynamic of a team can make a tremendous difference in the way that problems are solved, challenges are addressed, and morale is maintained. It has a huge effect on the atmosphere of the whole endeavor. The team at the Tut River camp were all intelligent, driven, resilient, and passionate about wildlife.

The full-season team was relatively small, with only four members who were joined by occasional guests (such as the previous camp lead, a renowned wildlife photographer, the project’s original Principal Investigator, and myself). The camp swelled significantly at the end of the season, however, during the final phase of research when the Principal Investigator, graduate students, and biologists from U.S. Fish and Wildlife Services all joined to help band geese (more on that later).

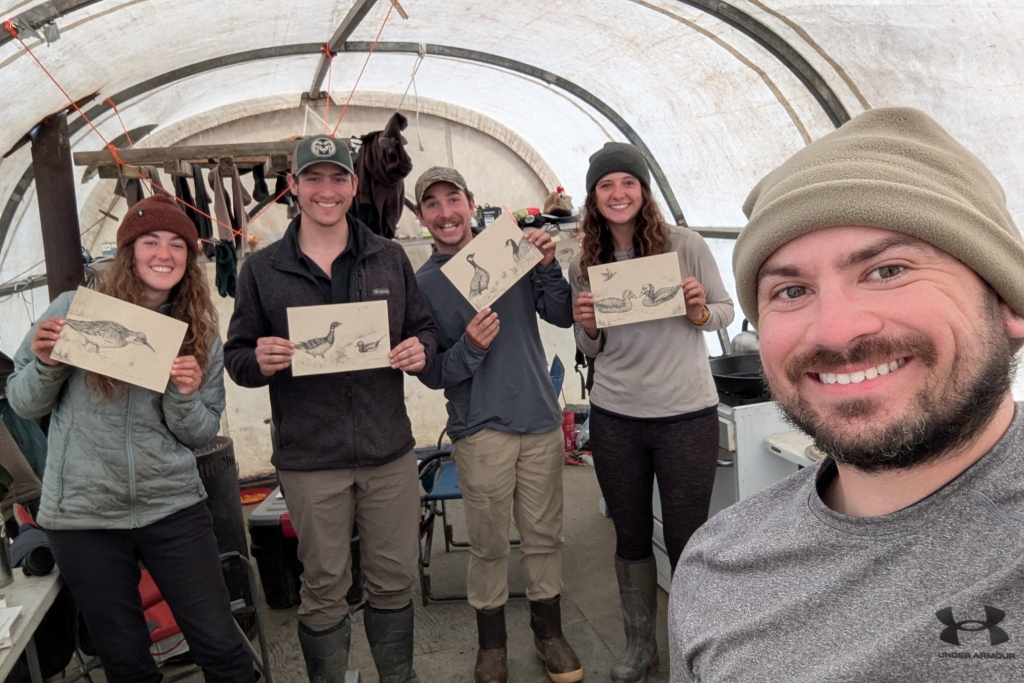

The primary Tut crew was led by James, who is a Ph.D. student studying under the project’s Principal Investigator, Dr. Dave Koons. Ilene and Dekka are both research technicians holding degrees in biology who were selected to assist with the gathering of data for this season and have impressive resumes with wildlife initiatives around the country. And rounding out the Tut crew was Bella, an undergraduate researcher who is in the final stretch of completing a bachelors in biology. These four intrepid and adventurous team members lived in the solitude and sometimes challenging conditions of the tundra from the beginning of May through the end of July.

I’ve been fortunate to be a member of many teams in my professional career, but – and this is not hyperbole – the camaraderie and cohesion of the Tut Crew was one of the most special I’ve ever seen. It is rare to find a team that supports each other so thoroughly and gels together so well. Their efficiency and competence in the work they were doing was matched only by the silliness and fun-loving demeanor they had when it was time to play.

The brant project as a whole is helmed by Principal Investigator, Dr. Dave Koons, who was incredibly generous with his time and expertise as he contextualized the research and helped me prepare for field in the months leading up to my time in Alaska.

While the full-season field crew itself was relatively small, the people required to make the whole endeavor possible extends across Federal institutions, universities, private companies, and a superstructure of dedicated scientists, biologists, logistics organizers, and indigenous communities all helping support the research for brant geese. This emphasizes that fact that science does not exist in a vacuum, and it is incredible to see how so many various groups are able to come together in pursuit of greater understanding of the natural world out of a desire to preserve it.

It also needs to be said that my time in camp wouldn’t have been possible if it wasn’t for the outstanding team at Polar STEAM. The prep-work and discussions with the cohort of Polar STEAM fellows, the logistics and planning meetings, and the support every step of the way from Polar STEAM’s team made the prep time and time in camp a seamless process.

Life in a Remote Field Camp

One of the most beautiful things about the location of the Tutakoke Field Camp was how truly remote it was. Situated on Cup’ik and Yup’ik lands, the camp was also within the Yukon Delta National Wildlife Refuge which was established to help protect this vital nesting site for many bird species. The nearest settlement to the camp site, the Cup’ik village of Chevak, was two hours away by boat if the waters were calm and considerably longer if they were not. No roads stretch across the tundra, and villages are accessible only by plane, helicopter, or boat.

The camp, which is set up each May, has supplies cached via snowmobile in the winter and sling loads brought in by helicopter when the researchers arrive for the season in spring. The camp consisted of two Weatherport shelters, a plywood outhouse, a plywood makeshift sauna, and rugged outdoor tents.

Day to day in the Alaskan camp looked very different than my usual day to day at the science center nestled in a mid-sized city in the south. One of the Weatherport shelters served as, more or less, home. It was a hub for various aspects of our lives. It served as an office space for data entry, our kitchen, and our cozy communal living room for unwinding after long treks in the tundra. It was outfitted with a solar panel with a battery, oven and stove combination, small freezer, and a heater that helped provide a small respite from the cold. The other Weatherport stored gear, equipment, and food.

At the end of each day in the field, we would drop our gear and get to work on the camp chores which included topping off the drinking water cooler, collecting wood for the sauna (the closest thing we could get to a shower), checking on the boats, inputting field data, and prepping any equipment that may be needed in the coming days.

Once chores were done, my first order of business was to swap out of what I referred to as my “tundra clothes,” which, for lack of a more eloquent description, were about as gross as you’d expect from an outfit that endured hours of mud, sweat, and seawater for several weeks. One thing that is easy to take for granted is the ability to have a hot shower with pressurized water. Our bathing consisted of baby wipes and, if the weather cooperated and we could find wood, a sauna which let us sweat in the steam and pour Dawn dish soap on our heads, though this was a rare treat that happened once a week if we were lucky.

After chores, we were then free to enjoy some time to prepare dinner, turn on the battery-powered radio, and relax a little. We rotated cooking responsibilities everyday, with someone always volunteering to cook for the night, usually with an idea in mind from the rumbling stomachs while we were out in the field. Whoever cooked that night never had to worry about doing the dishes since volunteers always took that role (quick aside, washing dishes was a fascinating process involving soap, a kettle, two small totes, and pot full of pond water).

At night – as much as it could be called that since the sun never dropped below the horizon – we would play card games, tell stories, or if we’d had a particularly sunny day and the solar battery was fully charged, we would watch a movie on a laptop with a small speaker attached to it.

The love the team had for wildlife often blended into creativity as well. We would take our cameras out and just enjoy the opportunity to be in such a remote spot that was teeming with life. We also made a lot of use out of sketch paper and drawing pencils. There was something magical about sitting around, talking with each other, as we sketched away against a soundtrack of bird calls and the hushed ripples of the Tut.

There was an extremely stark difference between my usual everyday experience and that of the Alaskan tundra. It was way more physically demanding, I was either drenched in sweat or shivering with very little in the middle, and our only modes of connection with the rest of the world were from an emergency satellite phone, an InReach GPS that could be used for “I’m safe” texts and occasional short phone calls, and the radio stations of Nome and Bethel. And I loved every minute of it.

There was something so refreshing about not being inundated with emails and having to juggle the frenetic pace of the professional world with necessities of errands while also carving out enough time for hobbies and socialization. It was liberating just being able to exist in that moment. There were many times I found myself laying down, camera in hand, watching all the birds dancing across the sky and speaking in their incomprehensible way. I enjoyed being untethered for several weeks so much that it is something I intend on doing at least annually to help recalibrate and reset.

With the team and life in camp established, Part 3 of this blog will go into what the team was there to do. The research being conducted is important for a thriving ecosystem not only in the Alaskan tundra, but around the entire world.