Before leaving for my Polar STEAM adventure to Greenland, I went to a poetry reading by a friend and colleague, Jenn Derilo. She read a poem about the color blue that was inspired by the poem Yellow by Charles Wright. Like so many of Jenn’s poems, it started off going in one direction and it ended up in a totally different place than I had expected, which is not unlike how Greenland got its name in the first place.

Many of us have heard that Greenland is a misnomer, a name attached by Erik the Red to attract Norse settlers in the Middle Ages. The story goes he was exiled from present-day Iceland for murder and created the first Viking settlement in 982 CE. Locally, Greenland is known as Kalaallit Nunaat—home of the Greenlanders, a culturally diverse group of Inuit peoples who migrated from the North American continent in different waves beginning more than 4,000 years ago and as recently as about 900 years ago. Now, Greenlanders have autonomous rule as a territory of Denmark, where the island is known as Grønland. According to the National Snow and Ice Data Center, an ice sheet covers 80% of Greenland. This is equivalent to two Texases and one New Mexico, combined. Granted, that’s a funny way to compare place sizes, but not as funny as calling a place a name that, while rooted in a history, does not tell the story of the planet’s largest island very well.

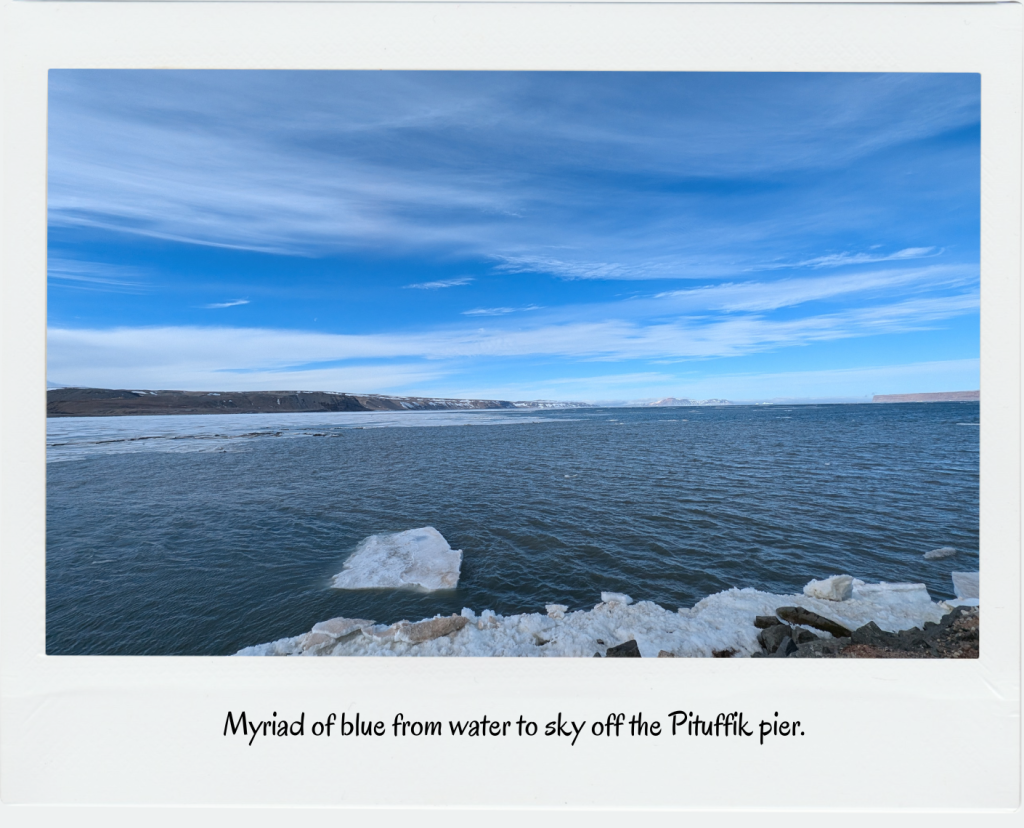

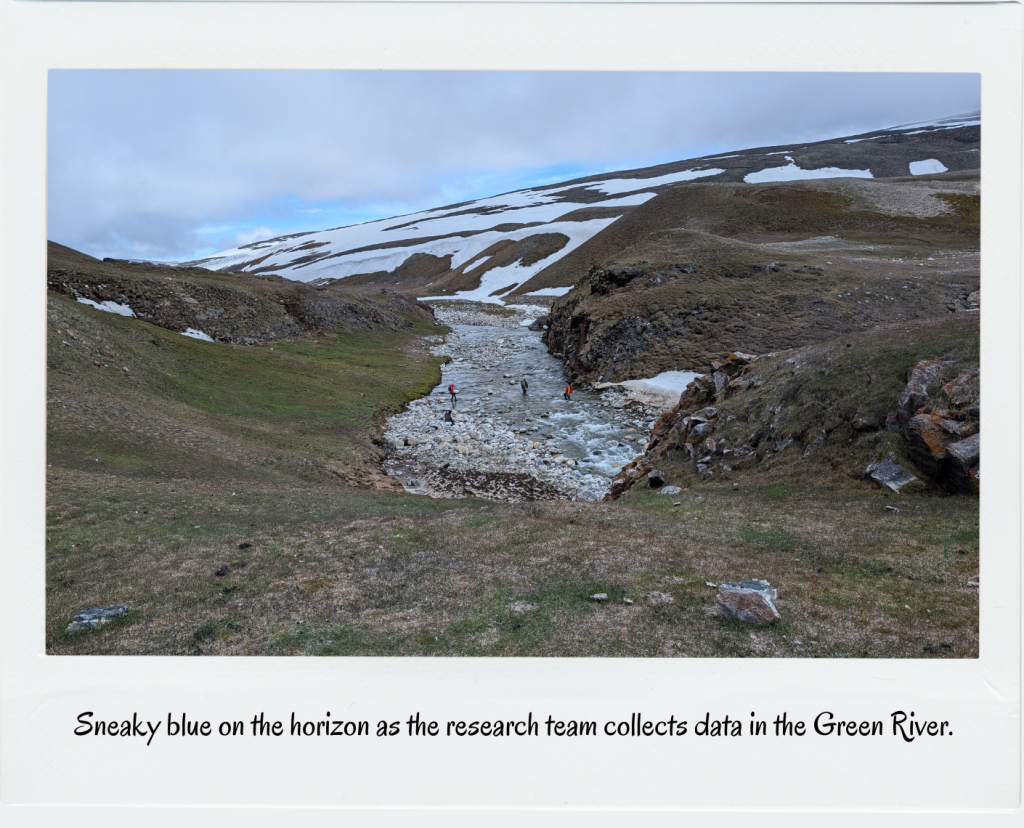

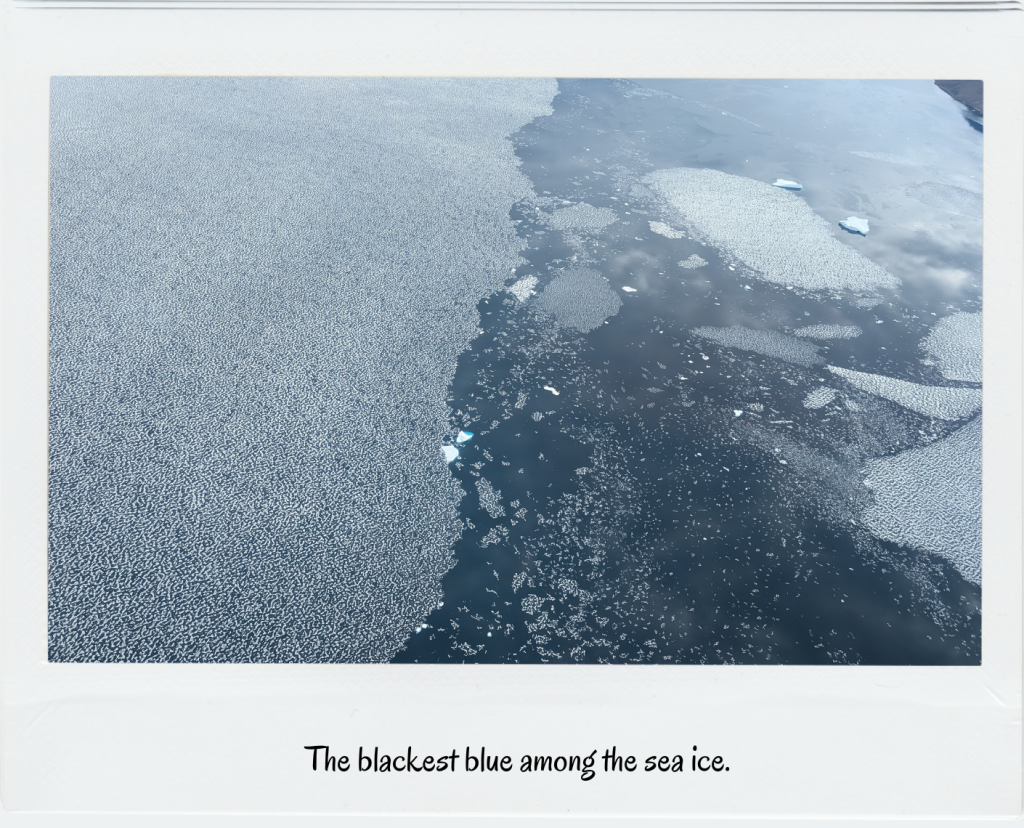

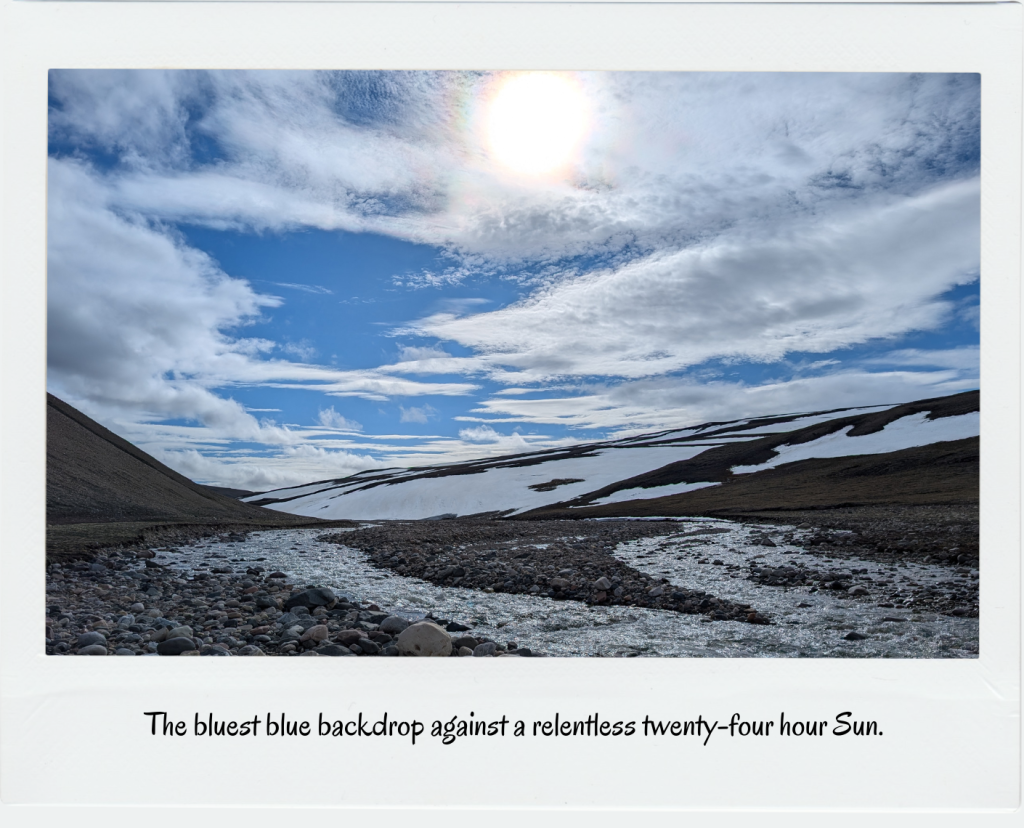

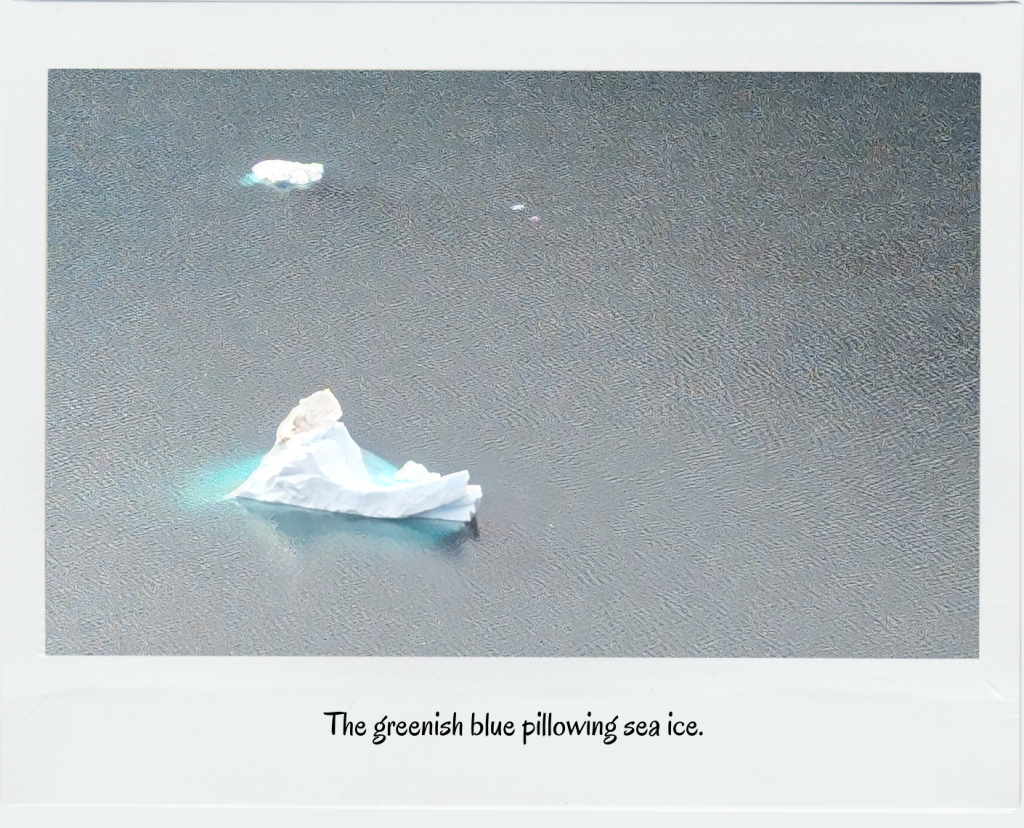

Getting back to the poems using a color as a theme, I thought I had seen all of the colors of blue before my trip to the Far North. After all, I teach about the electromagnetic spectrum and the active and passive sensors that scientists use to understand our changing planet. And yet. There were blues in Kalaallit Nunaat that I had never seen before. While photographs don’t really capture the vibrancy of the colors, or the feeling of being there, they are a starting point for conveying what I mean.

I learned a lot about the doing of science during my time with the Follow the Water research team. Installing instruments in or near the active layer—the soil found above permafrost that thaws and freezes seasonally—is no easy feat. A lot of creative problem-solving goes into finding a good site that will withstand the winter with four months of sub-zero degree Fahrenheit temperatures. “You can never have too many pipe clamps” was one lesson learned.

In Kalaallit Nunaat, I had time to reflect on the differences between how I teach about science and how research scientists approach their work. I think we’re all storytellers. When teaching about the complexities of Earth systems, I often tell my students that I’m lying to them. To explain the seasons, I say that the Earth’s axial tilt is 23.5° but in reality it’s roughly 23.43607°. And, I cover the reservoirs and pathways that water molecules travel when introducing them to the water cycle. But in all these years I’ve been teaching, I’ve omitted the complexities of groundwater flow in the Arctic Water Cycle (supra-, intra-, and sub-permafrost groundwater flow). I’ve oversimplified the story that I’m telling my students about the Earth.

When asking Eric (PI) or Logan (PhD student) from the Follow the Water research team about the features on the tundra landscape, questions like “Was this hillside created by a slump?” or “Is this wetland caused by thawing permafrost”, they would reply with some variation of “maybe”. As research scientists, they were hesitant to tell the story of the landscape without data or evidence to support their claims. Once they have their five years of data, they will be able to tell the story of permafrost hydrology in the Far North of Greenland. I counted twenty-five different variables that will be tested in the water and soil samples collected, and I’m probably missing a few. Using isotope analysis, for example, they will be able to understand the Arctic Water Cycle and whether water samples originated from the Greenland Ice Sheet or another location. It’s a story never told before in this part of the planet, a location that is changing rapidly.

Thanks to the Follow the Water research team members who were in Greenland during my time there, the PolarSTEAM team for giving me this incredible opportunity and guiding me throughout, to Polar Field Services for the gear and to the U.S. National Science Foundation for the funding, and to Jenn Derilo for inspiration to tell my story.