Tuesday, Apr 2, 2024

Today we got set up and met the local 8th graders out on the ice! For some of them it was the first time they had been on the land-fast sea ice (which is ice that is “fastened” to the coastline). For some, it was old news. It was quite cold (-30F with the windchill), so many students hid in the tents we had set up. The previous days had been relatively warm, hovering around 0-10F degrees. The students were split into groups and rotated between the stations.

Billy, an Iñupiat elder and North Slope wildlife officer, talks to us about how the whales move near the coast. The map he drew shows how the whales move, basically jumping from point to point where the land-fast sea ice meets the open water. That boundary is currently between 1 1/2 and 3 miles from land, depending on where you are.

We practiced harpooning the model of a Bowhead whale. The black humps represent the 2 humps of the whale. These whales pass by Utqiagvik from late April to early June. The state of Alaska has a limit of 100 strikes each year. Different native areas or villages get a portion of that, so Utqiagvik gets 25 strikes, or whales that they can kill, each year. They regularly fill their quota. Usually, it only takes 1 or 2 hits from the harpoon to kill the whale. Then they have to drag it on shore. An adult whale can be about 100,000-120,000 pounds.

At another station, students learned about albedo, or the reflectivity of a surface. The scientists had a tool that measured the albedo, so some volunteers lay down and we measured the albedo of their jackets. For some reference, a white object has an albedo of 0, and a black object has an albedo of 1. All other colors are somewhere between that. Climate scientists care about albedo since a light surface will reflect more light (and heat), whereas a dark surface will absorb more light (and heat). People are worried about a positive feedback loop happening, where the melting sea ice is replaced by dark ocean water, which absorbs more heat and causes more ice to melt, which means there is more dark ocean water that absorbs more heat.

Here we are in a tent with a hole that we dug with an auger. We put a camera down the hole and could see the bottom of the ice, then we dropped it further and we hit the bottom. The kids were like “Woah. That’s pretty cool”.

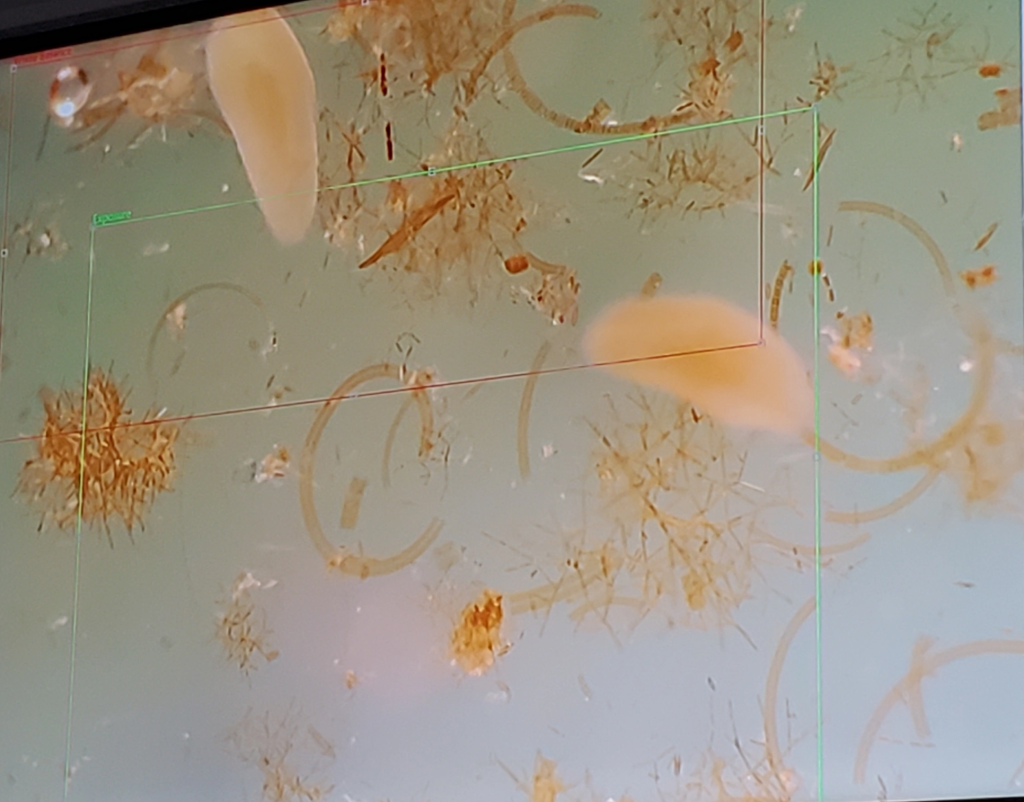

Back at the field station, we got a chance to look at the algae and worms that we collected by drilling into the ice. They live in the couple of centimeters at the bottom of the sea ice where it meets the ocean water. Most of what can be seen in these pictures are diatoms, a photosynthetic organism. Pretty cool that they can photosynthesize through 3 feet of sea ice. In the picture, there are multiple worms (the slightly oblong smooth-sided things) that are a new species that Kyle is describing. In fact, there are a couple of different species that have yet to be named that he is working on. Also swimming around in this microscopic world were some rotifers and dinoflagellates. Kyle and Gwen, both from the University of Alaska Fairbanks, were intrigued by one of the dinoflagellates, which they said looked like the species “Alexandria” but had never been recorded this far north. Possibly it was a new species. Alexandria is interesting because it is what causes shellfish poisoning (as in “Red tide”). Gwen says that even a hundred or so of this species (which again, are microscopic) in some shellfish will poison you.

It was a great day of learning for all out on the ice!